Former World War I National Filling Factory

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the filling facilities for high explosives were limited to the Royal Arsenal Woolwich and factories at Lemington Point and Derwenthaugh (Newcastle Upon Tyne), belonging to the armament manufacturers Armstrong and Whitworth and Co. Ltd. By 1915, the British Army found itself on the Western Front with insufficient ammunition; the demand for filled shells exceeded production. The National Filling Factories (NFF) were conceived by the new Ministry of Munitions, formed under Lloyd George in June 1915. Their layout utilised elements of modern factory production with a logical flow of materials and a production line. Principles of scientific management were applied to the workforce including ‘dilution’, where skilled work was broken down into individual repetitive tasks which could be performed by unskilled or semi-skilled labour. In the NFFs this meant the innovative use of female labour which reached 90% of the total labour force in some factories.

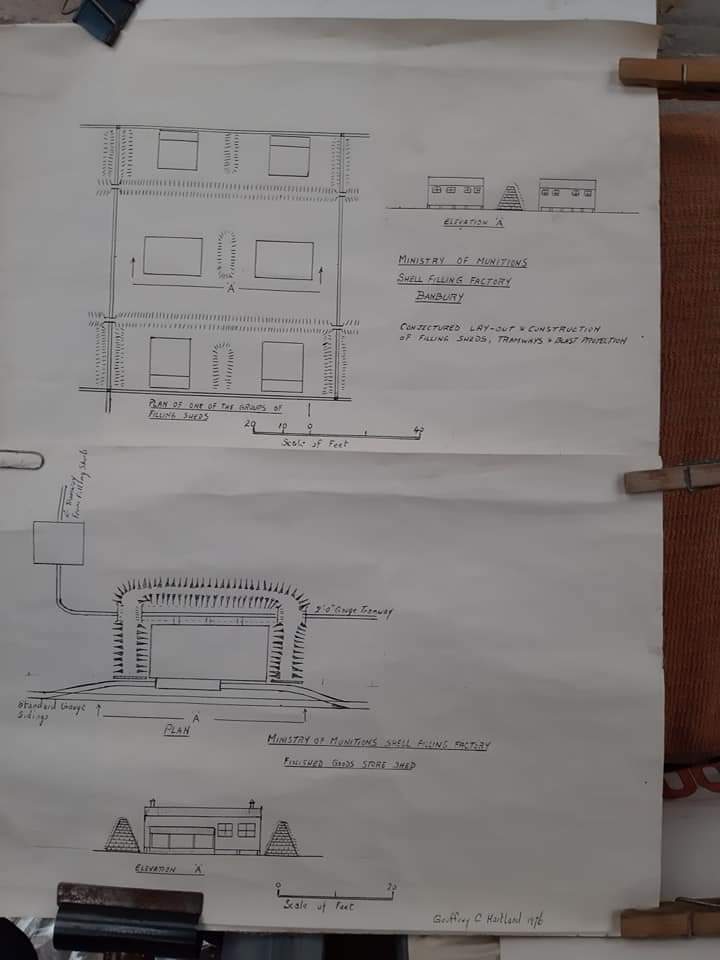

Though part of a national network financed by the government, there was no rigid design template imposed on each site. Certain principles were laid down following good practice at Royal Arsenal Woolwich, but many aspects of the Home Office guidelines were relaxed. Plan form was influenced by topography and the architect’s own ideas. Four explosives filling factories, including that at Banbury, were designed, built and managed by their managing directors but the construction of the factories generally depended on local firms, though the Office of Works erected those at Banbury and Perivale (London).

NFF Banbury, Northamptonshire, was one of the earliest purpose built by the Ministry of Munitions and was known as NFF No.9. It was commissioned in November 1915 and responsibility for its construction and management was given to Mr Herbert Bing, and the building contract was let in January 1916, to Messrs Willet of Sloane Square. The first lyddite was run on 25 April 1916. Initially the factory comprised only the northerly No. 1 Unit, designed to fill 100 tons of lyditte per week. In 1916 over 1400 local people were employed, a third of them women. The basic operation of the filling factory is evident in the plan. Empty components were bought into one side of the unit and the explosives into the other side, and the filled shells were moved to a storage magazine before they were either moved off-site or moved for temporary storage in an Army Ordnance Department store. Shells were moved between production areas by an internal tramway. Inside the factory were box stores and the empty-shell store, where on arrival the empty shells were cleaned and painted before they were issued to the filling houses. At the centre is a series of 22 melt houses which served eight filling sheds. Picric acid for melting was held on the eastern side of the group in long sheds and when ready for use, it was bought into the stores at the southern end of the group and then sifted before melting. After filling, the shells were moved by tramway to the two filled-shell magazines to the east.

The factory’s capacity was doubled with the construction of No.2 Unit to the south giving a total area of 132 acres. This was built within a year or so of the No.1 Unit. Experience in operating the first unit brought modifications to improve the flow of materials through the second, including a clearer flow of materials from the empty shells stores on the south western side, through the paint shops to the filling houses, and on the opposite side from the long picric acid stores through the sifting houses to the melting houses.

On May 30th, 1917 a notice was issued to the effect that all shells used by the British batteries in the battle on the Italian front came from No.9 Filling Factory. the quality of the ammunition that was produced was highly praised and factory employees were encouraged and exhorted to continue their good work (Lester, 1983).

When demand for lyddite declined by September 1917 as the army switched to TNT, sections of the factory were converted to filling naval mines and shrapnel shells and, early in 1918, part of the factory was given over to the filling of chemical shells with mustard gas although it is unclear which sections were affected. Around 1919 the factory was purchased by Cohen of London who used it for breaking down surplus war ammunition. This activity continued until 1924 when the factory closed. It is believed that the factory underwent ‘thermal remediation’ (sections of the site were deliberately burnt) which was the standard way of ensuring that no explosive residuals were left in former explosives handling buildings. It is possibly that it was this action which reduced the buildings and contributed to the formation of earthworks.

During the Second World War the site of the abandoned factory is believed to have been used as a military training area although no field evidence of purposely dug trenches or other training features was identified on site.

The site of the Filling Factory at Banbury (Unit no.1) survives as a series of well defined earthwork, standing and buried remains, and is currently used as rough grazing for cattle. The monument has been truncated by the M40 motorway, which has obliterated elements on the extreme western side of Unit no.1.

The site is protected by Historic England designation as a Scheduled Monument as it is considered to be of national archaeological importance